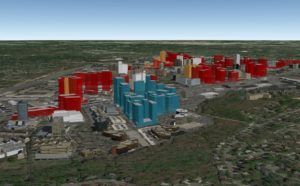

Tysons faces a major obstacle to converting itself from a suburban office park to urban community, and it is the lingering scale and design of the road network in town. It won’t shock anyone that major roadways designed around vehicles only have a tendency of reducing pedestrian access. Furthermore when intersections are spaced on quarter mile intervals instead of traditional 200 foot and 400 foot segments, these wide roads deteriorate any adjacent pedestrian access by acting as barriers blocking people that are on one side of the roadway to the other side of the roadway.

There are places in the world that have found a balance between vehicle and pedestrian access, and it doesn’t always mean creating the traditional “human scale” infrastructure that one might find in an old colonial town. New York City’s avenues, London’s circles, and Tokyo’s high tech corridors are examples of where big infrastructure doesn’t dissuade pedestrians.

Part of the reason why pedestrians still walk, cross, and all together enjoy these zones is because they have no choice. There are millions of people who live in these cities, and people are everywhere including the major thoroughfares. But it’s also because, despite the more rapid access for vehicles on these major roads, there is still a significant consideration to pedestrians. Intersections are spaced appropriately, allowing easy crossings for those on foot. This is often objected to by drivers, and all too often transportation planners, because each light is seen as a delay to drivers, as opposed to access for pedestrians.

Off of these major roadways are where enclaves of truly walkable spaces can exist. Without pseudo-highways obstructing access to these zones, people are able to cross the major roadways to get to these walkable neighborhoods. An example of a successful implementation of this is Harajuku Tokyo. Major roadways criss-cross along every border of Harajuku, but because of proper spacing of intersections to cross these roads, people can get to walkable places like Takeshita Street. If the major thoroughfare were designed around limited access, zones like Harajuku — a cultural and commercial hub in Tokyo — could never exist. The main economic driver for these communities is foot traffic.

Another means to making major infrastructure walkable is restricting vehicle access all together. Sacrilege! The reality is that most roadways, especially those in Tysons, are designed for peak travel periods — the couple hours during weekdays when commuters create the greatest demand. The remaining hours during the day, and especially those during the weekend, leave these areas not only barren of people due to improper pedestrian design, but devoid of cars as well. To create better walkability in these corridors requires a proper road grid in order to provide detours to the remaining off-peak vehicles during restricted hours.

Focusing on old world design standards as the only means for transitioning urban zones is as flawed a concept as focusing on vehicle only considerations in infrastructure planning. Places like Tysons, or former vehicle-hubs like Arlington (formerly known to many as Carlington), will never look and feel like a Paris, Florence, or Prague. They can’t collapse to a scale like Old Town Alexandria or Georgetown. These older communities were planned and built before the industrial age. The examples we should look to are post-industrial urban centers like Tokyo which have found a means to balance all transportation modes.