As a lot of walkers have noticed in Central Tysons the closer you get to Tysons metro station, the less walkable it gets. There are two factors contributing to this, one is the obvious lack of public pedestrian infrastructure beyond cursory sidewalks. The second is getting the human scale back in the development pattern by reducing setbacks with infill small height construction.

At the main intersection of Tysons Boulevard and Westpark Drive there continues to be a super intersection created with highway on-ramps in mind rather than pedestrian access to the central transit center in Tysons. This despite over two years of complaining, media mockery, and capitulation that changes would be made — to no avail.

There remains only 2 crosswalks at this main intersection, despite the goal for Tysons being a transit accessible place. It’s not a good sign when the very block the transit is located is not accessible for most people.

Removing the double turn lane solves the core problem of the intersection, and reclaims nearly 2000 square feet. This would also makes it possible for some retail space to fill in the newly opened area. By providing a wider sidewalk and this lower height massing the road itself will seem less canyon-like.

There is nothing uniquely wide or barrier-like about Tysons Boulevard itself; most of the street is only two lanes each way, similar to many in very urban areas. The barrier begins at intersections where double stacking and double turn movements are being implemented. A consistent two lane each way section would also help in the goal of walkability, but that may not be politically feasible given commuter sentiment.

Other locations that transformed from more suburban to urban planning patterns have been successful with implementing micro-development, to reduce “office park” setbacks. In the DC Metro region, Bethesda’s main strip of retail along Bethesda Boulevard was a very similar condition, and has really created a walker’s paradise, in some cases with shops less than 20 feet in depth.

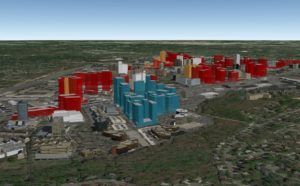

Addressing both the infrastructure side, and the “things to do” side of walkability helps encourage more pedestrian use. Optics are critical as well, with deep setbacks from already wide street sections — especially at intersections– a road like Tysons Boulevard can begin to look more like a high-speed suburban thoroughfare.

The goal is a walkable core for what Fairfax County wants to be a future urban Tysons. Allowing infill development will help mature portions of Tysons without creating unused glut, and adapt the existing parcels into a walkable human scale.